This is an interview with Phil Cohen, a pilot in the famed “Pioneer Mustang” Fighter Group during World War 2. It’s a candid view on some of his experiences during the war.

Oral History:

Phil Cohen, P-51 Mustang Pilot

by Jesús Dapena

(email: dapena@iu.edu)

(photo courtesy of 354thpmfg.com)

(edited by Jesús Dapena from a conversation taped in Highland Park, Illinois, on May 25, 1999)

Civilian Background

Phil Cohen was born in Chicago on May 13, 1923. He was very close to his father, who had emigrated to the United States from Russia. Phil liked to play baseball, and he was good at it. He was also a Sigma Epsilon student at Hyde Park High School, from which he graduated in 1941. He attended Wilson Junior College in Chicago before joining the U.S. Army Air Force.

Summary of Military Service

After completing his flight training at Bartow Airfield, Florida, he was shipped to England. In January of 1944, he was posted to the 353rd Squadron of the elite 354th “Pioneer Mustang” Fighter Group of the 9th U.S. Army Air Force as one of the first replacement pilots. He was first stationed at Boxted, a very small town between Colchester and London. Later on, Phil’s unit moved to Headcorn, southeast of London. After D-Day, he was based in an airfield called A2, 11 or 12 miles south of Omaha Beach. Phil flew a total of 63 combat missions. He downed three Messerschmitt Bf-109s, and one Focke Wulf FW-190. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal with twelve oak leaf clusters, an ETO with four battle stars, and presidential citations.

(graphics courtesy of 354thpmfg.com)

Phil's Planes

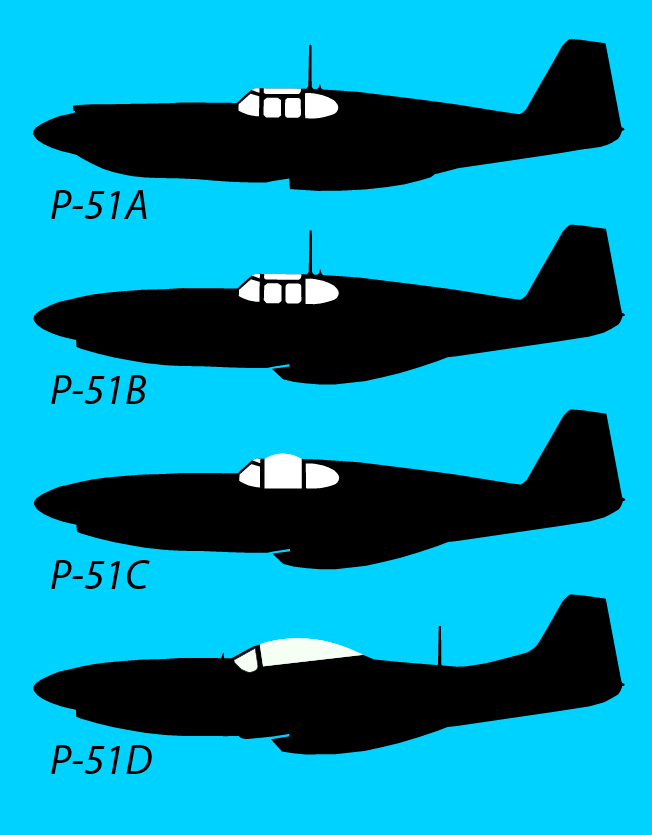

Phil flew four types of planes, all Mustangs: P-51A, P-51B, P-51C and P-51D. He flew the P-51A during training at Bartow Field in Florida. It was equipped with an Allison engine. The other three planes had Rolls Royce Merlin engines (license-built by Packard), and he flew them in combat in Europe. The canopy of Phil’s P-51B was identical to that of the P-51A, while his P-51C was fitted with a bulging canopy (“Malcolm Hood”) similar to the one used by most British Spitfires. The P-51D had an all-round-vision bubble-type canopy. Phil’s plane was marked with the letters “FT-D”, and it was called the “Flying Joker”.

-How good was visibility toward the rear in the P-51B?

-I had a mirror outside the cockpit.

-Were those mirrors very effective?

-[shakes his head] The mirror had no adjustment. I tell you that you could not see anything. They should have just taken the mirror off! [laughs] In the P-51D the mirror had no use at all, but it was a million times better than in the B plane.

-So it was still bad in the P-51D?

-Yes.

-Why was the mirror bad?

-Because it was useless in the air!

-In the P-51D, with the bubble canopy, could you just turn your head and look back? Or did the head rest obscure a lot of the view?

-In the P-51D you could look back, yeah.

-It was good?

-Yeah, yeah.

-So the fact that you had a backrest there did not obstruct the view a lot?

-Yeah.

-But in the P-51B, if you turned back, could you see anything?

-In the B plane you could see nothing. Nothing.

-Could you see better in the P-51C than on the B?

-Much, much better.

-So the Spitfire kind of canopy helped a lot?

-Yes. You could turn your head and look back.

First Mission

-Phil, tell me about your first mission.

-My first mission was from Boxted, England. I escorted B-17s and B-24s to Berlin. I was at 23,000 feet, and I was cold. I couldn’t find the heater. Six hours later, I landed, and my toes were so cold! I got out of the P-51, and I asked, “Where is the heater?” “The heater is right on the cockpit!” For 30 minutes, I hung my socks and shoes up, and I bathed my feet in warm water.

Distinguished Flying Cross

-What about the flight in which you downed two German planes?

-I was a flight leader of four P-51s. There were sixteen P-51s in this squadron, and I was in a fighter unit of four. We had escorted bombers to Karlsruhe, Germany, and were on the way home. I was at 23,000 feet. We had belly tanks, with 75 gallons a can.

-Wing tanks?

-Yeah, on the wings. 150 gallons of belly tank. Way in front of us there was a group of 30 Messerschmitts, and I got two of them.

-Were they at lower altitude than you were?

-Yes. I raised the altitude of my four planes to 25,000 feet, and they were at 21,000 feet.

-Were they heading in the same direction as you?

-We were all heading West.

-Did you close in pretty quickly onto the enemy planes, or was it gradual?

-Very gradual. I had 300 miles airspeed, and the Messerschmitts were traveling at 250 miles airspeed. Very fast, very very fast. I switched on the guns, and opened up on a Messerschmitt with all six guns. I went “boom, boom, boom, boom” [imitates four bursts in a total time of about two seconds]. The right landing gear of the Messerschmitt dropped, and I knew that I had made a hit. I had shot down a German plane. There were German planes all around us, and my wingman shot down another German plane. He was on my tail. My wingman was Lieutenant McKenney.

-So when you shot, you usually made short bursts?

-Yes.

-How long? Like what you just did?

-“Boop, boop, boop!” [imitates three bursts in a total time of about 1.5 seconds] We had six .50 caliber machine guns. Every fifth round was an API (Armor Piercing Incendiary) bullet, for hitting tanks; the other four rounds were the regular .50 caliber.

-Why were the bursts so short?

-To prevent jamming.

-How did you get the second Messerschmitt?

-It passed right in front of me. I banked to my right, centered the Messerschmitt on my gunsight, and went “boom, boom, boom”, three bursts. I saw him blow up. I was a newcomer, and I had shot down two German planes! I was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

-About how close was this plane when you shot at it?

-Uh … 50 feet.

-50 feet? That is very close.

-Very, very close.

-Do you think either of these two guys saw you?

-No. They could not see me.

-You came from behind.

-Yes.

Gas Trouble

-Tell me about the time when you ran into trouble returning from a mission over Germany.

-On May 29, 1944, we had been on a mission over Leipzig, Germany, and were on our way back toward England, when we saw some Messerschmitts who were headed North. We chased them for about 100 miles, and then we attacked them. The Messerschmitts were at 21,000 or 22,000 feet, and I was about 2,000 feet above the Messerschmitts. I had my oxygen mask on. I flew at the first Messerschmitt, and I crippled him. He started diving down.

-Had he seen you?

-No, like the other two, he never saw me either. I was about 75 feet away from him when I opened up with my guns.

-Again, very close.

-Yeah, I was really close.

-All of them were very close.

-Yeah. We were told that if we shot from very far we would miss the target.

-So, what happened after you bounced the Messerschmitt?

-I followed him down. I followed him until he hit the ground. Then, I pulled on my stick, and got back up to 17,000 or 18,000 feet. I saw no friendly planes. I looked at the map, and I did not know where I was. Way in the distance, I thought I saw Belgium. But when I got there I saw that this wasn’t Belgium. It was the Zuider Zee! I was at 18,000 feet over the Zuider Zee. I looked at my fuel gauge, and I didn’t have enough gas to get back to England. I radioed, “Mayday, mayday, mayday!” A British voice came in, “What plane are you flying?” “P-51D.” “Are you hurt?” “No, I am not hurt.” “Why are you calling?” “I don’t have enough gas!” The British voice told me that if I followed his instructions I would be able to land in England.

-Sounds like a long glide.

-[laughs very loudly]

-I bet it was not this funny at the time! How high were you?

-18,000 feet.

-How far could you glide from that altitude? I know you still had a fair amount of gas, but if you had made a pure glide with the engine off, how far could you have gone? 18 miles??

-I don’t know.

-Who was this British guy that you were talking with?

-He was a follower of Allied airplanes. P-51s, P-47s, B-17s …

-So he was in a radio station somewhere in England?

-Yes, in a radar station in England. He showed me what to set in the manifold pressure, and in the throttle pressure. He told me how many feet I would drop per minute. I was over the Zuider Zee, with very little gas, and you have to keep in mind that I am a Jew … Thirty minutes beyond the Zuider Zee, I heard the British voice again, and he said, “Welcome to England.” And WAY in the distance, I saw England. I was at 10,000 feet.

-Do you remember how fast you were going during this gradual descent?

-230 miles, or 225 miles.

-Hmmm, that’s quite a fair amount of speed.

-Yeah.

-I see. It’s because you were not trying to maximize your time in the air; you were trying to maximize distance covered. So you needed to compromise between saving gas and maintaining speed.

-The British voice came back 5 minutes later, and said, “Go to that airdrome.” This wasn’t Headcorn. This was far from Headcorn.

-Hey, I’m sure you were willing to land in ANY field!

-I had 10 gallons of gas. My normal landing speed was 95 mph when I hit the ground. The trouble was my speed was 135 miles. For a normal landing, we would make a turn to the left, and then we would go in for the landing. But I had very little fuel left. After I stopped, a jeep instructed me to follow it on the ground. I saw P-51s, but this was the 8th Air Force and I was in the 9th Air Force. The field was right next to the North Sea.

-I bet! You didn’t go to Wales to land it, did you!

-[laughs] When I turned the engine off, it was about 12:30 in the afternoon. I talked to the fuel man, and I went to lunch. I had not had any breakfast. I had gotten up at 4 o’clock in the morning, and I had not had any breakfast.

-You went up in your plane into Germany without having had breakfast?

-Yes, except for a cup of coffee.

-Why was that?

-I overslept!

-Oh, OK!

-I had coffee again in the mess hall, and came back to my “FT-D”. I questioned the fuel man on how many gallons I had left. Two gallons of gas!! One gallon equals one minute. I telephoned Headcorn to report that I was OK. It was about 2 o’clock in the afternoon when I took off for Headcorn. I had to fly over London. I landed at Headcorn 45 minutes later.

A Guerrilla Pilot

-One of our lieutenants was with the FFI, the French Resistance.

-He was with them? What do you mean? He got shot down, and then joined them?

-Yes. He returned in August of 1944.

-How long was he in France?

-Four months.

D-Day

-Do you know if Mustangs were used on fighter-bomber missions around D-Day, or were those missions done mainly by P-47s?

-On June 6th, 1944, we woke up at 4 in the morning, and we knew that today would be D-Day. I went to my P-51, and I sat for 4 hours in the plane. As I looked up to the sky, I could see all the P-51s, P-47s, B-17s and B-24s. Then the replacement pilot came, and told me to go to sleep. At 6:30 in the evening, I was told that I would fly as a radioman with Colonel George Bickell, who was the commander of the 354th Fighter Group. I took off at 7 o’clock in the evening of June 6th, D-Day. We got to the Isle of Wight, in the South of England, and we waited for a 40-mile long stream of C-47s with glider planes. They were headed for Omaha Beach, and I escorted them there. The altitude of the escort planes was 1,500 feet.

(photo courtesy of 354thpmfg.com)

-Hmmm, that’s pretty low.

-That is very low! The C-47s and the gliders were at 1,000 feet.

-Did you have any higher escort?

-The sky was black. There was low cloud cover. Then, at 10:15 in the evening, Double British Summer Time (it didn’t get dark until 10:30 in the evening on Double British Summer Time), I saw Omaha. Our warships were shelling. The gliders landed at 10:30 in the evening, when it was getting dark. I didn’t see any of them; it was totally dark. Colonel Bickell then ordered us to turn around to go home, and told me to switch my radio channel to “A”. We were in “D” channel; I was the only radioman who went to “A”. I radioed, “Steeple Chase, Steeple Chase, Steeple Chase.” Steeple was a code name for “We are coming home”. In less than a second, Steeple Chase called me back, “DON’T COME HOME: It has been raining and raining and raining and raining and raining.” I switched then to “D” channel, and told Col. Bickell what Steeple Chase had said to me. It was now 11 o’clock in the evening. It was DARK! We were half-way over the English Channel, and there was no place to land!

-So the whole southern coast of England was overcast and rainy?

-Overcast, and the lights were out. The lights were out! Then Colonel Bickell told me to send out a radio message asking for help. Shortly afterward, we saw three search lights turned up toward the sky, and Colonel Bickell said, “That will be my base.” From our distance, I saw no base, but after I got closer I saw red, green … three searchlights. Green was “go ahead and land”; and red meant “too close for landing, get up”. Colonel Bickell was the first plane to land, and I was the second plane. In the landing field, I saw P-51s, but it was not our base. This was an 8th Air Force base, 150 or 175 miles due West from our airport. There were no barracks. I went to sleep in the mess hall. I don’t know where the other pilots went to sleep. I tried to sleep, but I couldn’t. At 5:30 in the morning, Colonel Bickell came in, and told us that we were going to fly to Omaha Beach. He didn’t go with us that day; he went back to Headcorn. I took off at 6 or 6:30, and flew to Omaha Beach with the commander of the field where we had landed; I don’t know his name. I carried two 500-lb bombs on the wings of my plane.

-So you flew a fighter-bomber mission on the day after D-Day.

-Yes, right on Omaha Beach. I saw German tanks, and I bombed them.

-With P-51s.

-Yes. But there were no connections between the P-51s and the infantry. There were absolutely none. And it was getting bad. I saw that 25 percent of the gliders had been wrecked. The servicemen had been killed. It was the only time that I thought, “We are going to lose this war.” Twenty-five percent of the gliders had been wrecked, and the infantrymen were dead. They were dead. It was the only time that I thought that. All the time we had been winning. 99 and 9 tenths of the time, we had been winning. But on this day, June 7th, 1944 … Jesus Christ! Bodies and bodies and bodies and bodies of U.S. infantry.

-You could see it from the plane?

-Yes. The planes dove to 1,000 feet. You could see all this from the plane. Finally, we got back to Headcorn, England. This was the base that we had taken off from on June 6th. We landed at 10 o’clock in the morning of June 7th.

A Flight with Ike

-I hear that Eisenhower once went flying with your outfit.

-I landed in France on June 21 or 22, 1944. I was a First Lieutenant. Our airfield in France was called A2. It was 11 or 12 miles South of Omaha Beach. General Eisenhower landed in a C-47 Dakota plane, and said he wanted to see the front line. The P-51 Mustang had no two-seaters, but the flight sergeant made a two-seater. He yanked the fuselage tank, and put in a dummy seat. I was on that mission, with General Eisenhower.

-Eisenhower was in the back seat?

-Yeah.

Flirting with Antiaircraft Fire

-Tell me about your ultra-low-level strafing run.

-I was six feet above the ground when I shot through a German tank truck and blew it up. I was flying only six feet above the ground because I knew that the German machine guns were not set up to shoot that low.

Deaths of Two COs

-One morning in August of 1944, our Commanding Officer, Major Don Beerbower, called a fighter-bomber mission to a German Air Force base in Belgium. I was on that mission. We had two bombs, one under each wing. Major Beerbower died. I dropped my two bombs, flew back up to 15,000 or 18,000 feet, and returned to A2. I jumped out of the plane at 10:30 to 11 o’clock in the morning. I told the Operations Officer that Major Beerbower had been shot. He said that he had heard that. He then told me that there would be another mission at 1 o’clock in the afternoon. I told him that I hadn’t slept for 32 or 33 hours. The OP officer told me to go to sleep. There are supposed to be 33 pilots in a squadron, and at that time we had only 15 or 16 pilots left because all of the 17 backup pilots were dead or had been sent home. I slept till 2:30 in the afternoon. Then I found out that Captain Wallace Emmer had been named the CO, and that he also had been shot. He had been CO for two hours. Beerbower was from Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Emmer was from St. Louis, Missouri. I knew both of them.

(photos courtesy of 354thpmfg.com)

After the War

When he returned to the United States, Phil went to school under the GI Bill. He had a very successful career as an insurance agent. Phil lived with his wife Pearle in Highland Park, Illinois. He passed away in 2002, and Pearle in 2012.