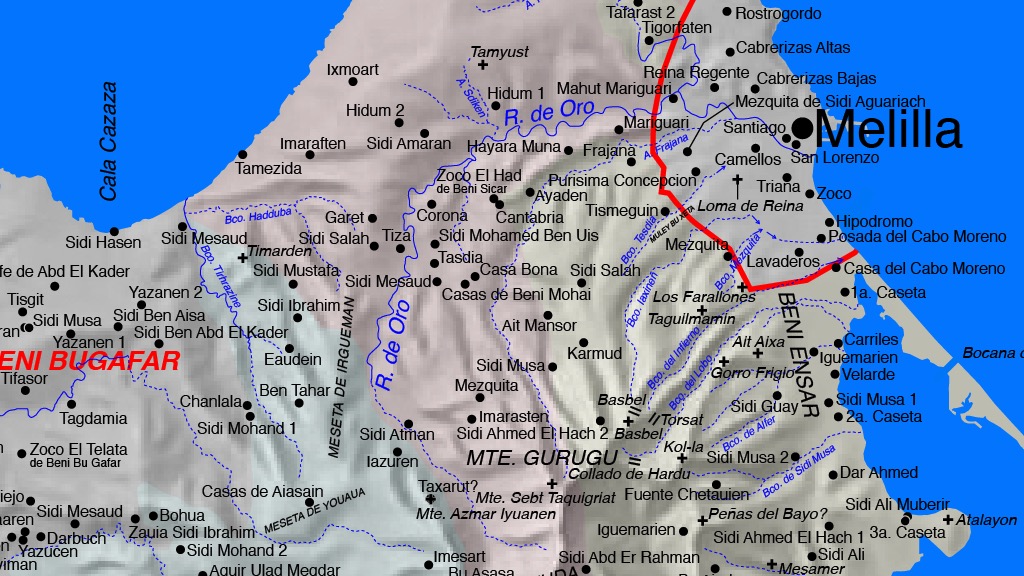

This map shows the military positions and other points of interest of the Rif War (1909-1927). It’s a historical resource designed to help researchers, students and other persons interested in following the campaigns of the Rif War.

A Map of Spain’s Early 20th Century War in Morocco

by Jesús Dapena

(email: dapena@iu.edu)

(Para ver esta página de web en ESPAÑOL, vete AQUÍ.)

Quickstart

The map can be viewed best if you make a right-click HERE, followed by a left- or right-click on “Download Linked File As …”. This will save the map pdf file to your computer. You can then open the downloaded file with Adobe Acrobat Reader, a free program that you can download through internet. (NOTE: Do not open the map pdf file directly on the internet browser using a left-click, because that could lead to problems. For instance, you may not be able to magnify the image enough to see the map properly.) You can increase or decrease the scale of the map image using the magnifying glass icons with respective “+” and “-” signs located at the lower right corner of the Adobe Acrobat Reader window. (After downloading the map pdf file, you can also open it with Adobe Illustrator, but this is an expensive program; if you don’t already have it, it will be best to use Adobe Acrobat Reader.)

Sample of a small section of the map

Detailed Information

I have always had difficulty finding appropriate maps for Spain’s early 20th century “Guerra de Marruecos” or “Guerra de Africa” or “Rif War”. There are two problems that often occur in the maps published in the literature of this war: (1) inaccurate locations of places, and (2) spelling inconsistencies of place names.

I believe that the origin of the problems was that much of the area had not been properly surveyed at the time of the war. The very border between the Spanish and French sectors of Morocco was to a great extent a fantasy, a line drawn on a map that was meaningless in many areas. It is not surprising that the Spanish and the French kept squabbling about where the border should be, with both rushing to occupy areas and produce a “fait accompli”. (I will briefly discuss the border further below.)

I assume that when the Spanish Army entered a new area, the soldiers and officers picked up the names of geographical locations verbally from the local villagers, transcribed them into Spanish as best they could, and made rough map sketches (“croquis”). Those map sketches and place names were then used not only by the Spanish Army, but also by the journalists reporting the war for the Spanish press. Different people heard the local sounds differently, and therefore it was normal to end up with several different spellings for the name of any single location. An extreme example is Sbu Sba/Sbu Sbaa/Sebu Sbaa/Buch Sbaa/Sbuch Sba/Sbuch Sbaa/Sbuch Sbach/Sbuh Sbah/Sebbux Es Sebaa/Sebuch Sbaa/Sebouch Sbaa/Zebbuya Es Sebaa/Zebbuy Sebaa/Zebbuy Sebas/Acebuche del Leon.

Ultimately, this resulted in inaccurate maps, and place names that varied from one map and publication to another. These problems have trickled down to many of today’s publications.

The goal of the present project was to produce a more accurate and useful map for readers interested in following the military operations of this war.

METHODOLOGY

My map is based mainly on three sets of previous maps:

(1) A shaded relief greyscale map of northern Morocco in the Web Mercator projection produced using SRTM data obtained from the Space Shuttle with radar technology. It was kindly provided to me by Tom Patterson of shadedrelief.com.

(2) A selection of 109 tiles of the 1:50,000 scale topographic “Carte du Maroc” published by the Institut Géographique National (Paris) and by the Division de la Carte (Rabat), mostly in the late 1960s and early 1970s. They cover the former Spanish Protectorate of Morocco and the north end of the former French Protectorate. I first found this excellent map collection in a website maintained by Dr. Rachid Bissour of Sultan Moulay Slimane University at Beni Mellal. That website later stopped working, but these maps –as well as other topo maps of Morocco– can be obtained HERE.

(3) The 117 tiles of the 1:50,000 scale topographic “Mapa Provisional (del Norte de Marruecos)” published by the Spanish Army. They cover the former Spanish Protectorate of Morocco. I looked for the most recent version of each tile. A version from between 1956 and 1959 was available for almost every tile. As already suggested by the term “provisional”, these Spanish maps were plotted with less accuracy than the French/Moroccan topo maps, but they show the kabila borders, as well as richer detail in village, mountain and river names. The individual maps can be downloaded from HERE. You need to enter in the “Búsqueda” box the name of one of the various regions of the Spanish zone of Morocco (Utauien, Yebala, Gomara, Ketama, Rif, or Kelaia). This search will give you many more maps than those in which you are interested; you will need to select the appropriate ones for download.

I also occasionally used information taken from the 14 tiles of the 1:100,000 scale “Mapa del Norte de Marruecos”, published by the Spanish Army between 1943 and 1947, which showed reasonable consistency with the “Mapa Provisional (del Norte de Marruecos)”. The 1918 1:100,000 scale “Mapa Militar” of the eastern war zone (5 tiles) is also surprisingly good considering its early date, while the corresponding map for the western war zone (1922/1924, 1 tile, 1:150,000 scale) is much less accurate, although still useful. The 1:100,000 scale “Mapa del Norte de Marruecos” and 1:150,000 scale “Mapa Militar” (western war zone) can be downloaded from the same website as the 1:50,000 scale Spanish Army maps by entering in the “Búsqueda” box the strings “Norte de Marruecos” and “Mapa Militar Marruecos”, respectively. Again, you will need to select the appropriate maps for download. The “Mapa Militar” (eastern war zone) can be downloaded from HERE; click on “Ver obra”.

Here is a summarized version of the basic process that I followed to prepare the map: I started by trimming the frame out of every one of the 109 French/Moroccan topo maps, leaving only the true map area. Then I used Adobe Illustrator to combine the individual tiles into a large mosaic. In this map mosaic, I marked the positions of the places of interest, and traced the rivers and the coastline. To correct for the differences in cartographical projection between the map mosaic and the shaded relief map, I also marked the locations of several hundred calibration landmarks (mainly hill and mountain peaks) in the two maps. Then I used Adobe Illustrator to construct a mesh consisting of the four corners of all the tiles of the mosaic map. By distorting this mesh, I made the calibration landmarks of the mosaic fit with their respective locations in the shaded relief map. I then applied the same distortions to the places of interest, the rivers, and the coastline, and finally I superimposed their positions on the shaded relief map. The Spanish Army topo maps were useful for adding the kabila borders, as well as points of interest that did not show up in the French/Moroccan topo maps.

The border between the Spanish and French zones presented a series of problems. At first, I assumed that the ragged bottom edge of the Spanish Army topo maps represented the border. However, I later realized that in most places it was merely the limit of the area surveyed by the Spanish Army. This border was ill-defined in the various treaties and agreements between the Spanish and French governments, and it also did not remain stationary, but generally crept northward in the course of the war. The Spanish and French governments often did not agree where the border was supposed to be. I found in Internet several Spanish maps that showed the border at various dates, but they were only rough and inaccurate sketches (“croquis”), usually drawn at small scales. (To see some of these maps, go HERE, and enter the string “trazado fronterizo” in the “Búsqueda” box.) The most detailed depiction of the border that I found in Internet was, surprisingly, in a map produced by the United States Army in 1953, and available HERE. It’s the 7th map in that web page, “Cartes 1 / 250 000 (U.S. Army 1953)”. It was based on earlier Spanish and French maps. The border of my map generally follows this American map from 1953, and it should be considered a reasonable but definitely imperfect representation of the position(s) of the border during the war.

USING THE MAP

Locations of places

The places that have no question marks after their names in the map are quite solid; they are points that I was able to locate in the trustworthy maps described above. The places with question marks are more doubtful; I took their approximate locations from maps in the literature. This allows us to know which place locations to believe and which ones are only rough approximations.

It’s not uncommon for some place names to be repeated in widely separate areas of the map. But sometimes the topo maps show the same place name repeated within a rather small area. I assumed that this meant that a village was spread out, and that the map simply repeated the village name at the various locations of the village’s house clusters. In these cases, I added an arbitrary number (1, 2, 3, …) after the place name to make the reader aware that this name occurred more than once within a small area.

Alternative place names:

As previously mentioned, place names can be searched on the map with your computer: If you open the map’s pdf file with Adobe Acrobat Reader or with Adobe Illustrator, you can type the name of any place, and the app will find it for you on the map. However, if the spelling that you use (the one taken from whatever book you are reading) is different from the one used by the map, you will obviously have a problem.

To get around this problem, I have put together a glossary of alternative place names. The name before the equal sign is an alternative name. The name after the equal sign is the one used in the map. You should first search for the place name in the map using the spelling from whichever book or article you are reading. If you don’t get any hits, search in the list below, and try the spelling that shows up after the equal sign.

I believe that most of the literature on this war is in Spanish. Therefore, I chose to make Spanish the basic language for the map. Also, I used for each place name the spelling that appeared to occur most commonly in the Spanish literature. This was not necessarily the most correct version of the name. For instance, “Zoco Es Sebt” (or even better, “Suk Es Sebt” or “Souk Es Sebt”) is the correct transliteration from Arabic of “Saturday Market”, but in the map I used “Zoco El Sebt”, which is the version that I found most frequently in the Spanish literature.

I have not used accent marks in the map nor in the glossary, for two reasons. The first one is that many publications omit the accents, or put them in an incorrect position, so using accent marks would be an additional hurdle for finding place names. The second reason is that in most cases I also don’t know where the accent should go!

I will continue making modifications to the map and adding alternative names to the glossary as new information becomes available.

If there is a place that you can’t find, please feel free to send me an email to dapena@iu.edu. I will try to help you to find it.

Translations of some geographical terms:

Finally, I made a listing of Moroccan geographical terms and their translations into Spanish and English. I took most of these terms from Gabriel Delbrel (pages 165-178) and from Francisco Martínez Yagües (pages 567-570).

Scale:

There is a 10 km scale at the lower right corner of the map. It may also be useful to know that the diameter of each small black dot on the map corresponds to 200 meters in real life, while the diameter of the larger black dots of the main towns corresponds to 500 meters in real life.

Please contact me (dapena@iu.edu) with any errors that you see in the map or in the glossary. Thank you!